900 index cards, first contact, conditions

In my first semester at the FernUniversität in Hagen, the relevant material for the “Introduction to Theoretical Philosophy” exam comprised about 1000 DIN A4 pages. Even after narrowing it down to 300 pages, dividing it into paragraphs resulted in approximately 900 index cards, each with an important line of thought of five key terms. One thing became clear to me very quickly: Memorizing everything the way we did in school, through rote, mindless cramming – NO, I would not do that. I would rather drop out!

I had already resigned myself to my decision when I came across the university magazine “Sprachrohr”. There, a fellow student mentioned the so-called Loki Method in an experience report, a mnemonic technique that represented my first contact with the art of memory. I immediately recognized its benefit for my studies in general and specifically for my upcoming exam and the stack of index cards. A first, quick review of relevant Wikipedia articles confirmed my hopes, and I decided to thoroughly delve into this art, with the help of the excellent guide „Einfach alles merken” by Ulrich Bien. This book still forms the basis and the point of orientation for my mnemonic technique skills. My instructional videos in this area serve two purposes: they are both condensations and, hopefully, clearer formulations of Bien’s explanations and a distillate of my personal experiences.

By now, there’s probably no mnemonic technique I’m not familiar with. If there is one, it must only be an insignificant variant. Starting with the smallest technique, the mnemonic, or memory aid, through the number-symbol route to the memory palace, we will gradually learn them all and apply them to your specific cases. Therefore, consider this video useful, even if you probably won’t need to memorize the symbols (cross, triangle, square, and circle) for any exam. I took it seriously and was ultimately able to memorize the initially daunting stack of index cards and much more relatively quickly and easily, passing my first university exam with an A and sparing my parents a great disappointment.

At this point, a few conditions without which success is unlikely: Memorizing requires deep-work conditions and a temporary retreat from drugs and passive media consumption, at least that was my experience.

5 Symbols, Limits of Normal Memorization

Triangle, cross, square, circle, triangle – this sequence of five abstract symbols, let’s call it Sequence-5, is easy to memorize. Although, like all my instructional videos, this one on meta-competencies.org also comes with tasks and exercises, it makes sense to pause the video and start attempting memorization right away.

Triangle, cross, square, circle, triangle, square, square, circle, triangle, triangle – a sequence twice as long (Sequence-10) is not so easily memorized by most people. They would fail just as they would with a phone number shouted out by someone they’ve just met in passing. In both cases, the total information consists of abstract elements: geometric figures and digits. Whether it’s a sequence of symbols, a phone number, or historical facts, the way we normally memorize such things remains a mystery. Between the information to be internalized and our memory lies a process we cannot further describe. Let’s call this type of memorization, memorizing without technique, as opposed to mnemonics and the conscious, systematic internalization. It is my preferred alternative: constructing information into the memory and deconstructing it again. In later, more detailed videos, we will discuss the workings in more detail and now continue with our sequence of symbols.

I promise, under the previously mentioned conditions and with sufficient seriousness, most people can quickly and easily memorize not only the Sequence-10 but also the exact order of no less than 100 symbols!

Visualizing, Locating, …

Just because we use these symbols here, don’t be afraid that we’re learning something useless. As mentioned before, the principles learned are applicable to all types of information, and I even used them for the not exactly visual field of philosophy.

1. We translate the symbols cross, triangle, square, and circle to make it easier. Since they appear multiple times in the Sequences 5,10 and 100, we use themes:

– The cross stands for the theme or the field of medicine. Such symbols are found on ambulances and at hospitals or with the Red Cross, which is also a mnemonic technique: a mnemonic aid.

– The triangle reminds us of the contours of a fir tree and stands for nature.

– The square stands for tools. Aren’t bollards unlocked with a square-headed key?

– Pizzas are round, so our circle stands for everything related to food.

Accordingly, the Sequence-5 would go something like: “Cactus spine, plaster, pliers, ice cream, fir tree.” The continuation in Sequence-10 might go: “… hammer, drill, kebab, lightning, thunder.“

2. Strictly speaking, the order of the individual symbols is also information. We use a ten-point sequence, which everyone already knows and therefore doesn’t need to memorize, namely the digit sequence 1 to 9 and finally 10. We just need to visualize them through objects that resemble the digits: 1 = arrow, 2 = swan, 3 = bra, 4 = sailboat, 5 = hook, 6 = open lock, 7 = crane, 8 = chain, 9 = balloon, 10 = all ten fingers or both hands. These ten objects in this order form the so-called number-symbol route.

3. Now we connect the translated symbols of the Sequence-10 with the individual objects of the route. The crucial part is to imagine these objects as if they actually existed, as if they were really there, with all senses: I touch the arrow, feel its sharp tip, it pricks, I run my thumb and forefinger from the tip down the shaft to the yielding feathers… It hits a cactus perfectly on a spine and splits it – that’s unique! And in this manner, we continue: The split spine is wrapped with a plaster. With pliers, I carefully pull both out of the cactus. With the help of ice cream, I preserve the proof of my dexterity and climb a fir tree. We could continue easily, but I promised to memorize the Sequence-100, and for that, the ten-point number-symbol route would be far too small.

4. We essentially increase the density by inventing a story from each set of ten visualized symbols and then connecting or gluing, intertwining, nesting, etc., this story with a point of the number-symbol route. We do this, as before, with the help of our imagination, which is limitless and always will be and on which we can mostly rely: “I injure myself on a cactus spine, so I put a plaster on it. Unfortunately, it still hurts because the spine is still in my finger, so I pull it out with pliers. As a reward for my bravery, I buy myself an ice cream. I don’t want to get injured like that again, so I climb a high fir tree for a better overview. To prevent slipping, I try to nail a few nails, which doesn’t work because it’s too heavy; so, I prefer to drill a few screws in. After the work is done, I eat a really tasty kebab at a lofty height. Just full, I’m surprised by lightning and thunder.” Oh yes, we want to start with the arrow, which is easy to reconstruct: “Someone shoots an arrow at me, I run off and injure myself on a cactus spine…“.

By imagining this story, I construct the Sequence-10 into my memory, and by recalling and visualizing it in front of my mind’s eye, I deconstruct it again. Unlike rote memorization through repetition, the process between external information and internal storage is now transparent, logical, and comprehensible.

5. For some, non-relevant elements of the story might be confusing. They could lead to the question when deconstructing: Is “someone” also a theme or a translated symbol, or the gained “overview” on the high fir tree? Therefore, I prefer a reduced, thus purified chain of each ten objects without nominally significant elements, laid out on a route point, which could roughly go like this: “Arrow hits cactus spine exactly. Plaster around split spine. With pliers, both out & preserve with ice cream. Stick it on top of fir tree. Strike with a hammer. Doesn’t work, so help with a drill. Wrap kebab wrapper foil around it; it attracts lightning and thunder.“

In this way, we proceed with the remaining 90 symbols, so we grab ten of them each and lay these ten-blocks on the individual points of the route, with the swan being the next storage location after the arrow.

Doubts, Assistance through AI

It wouldn’t surprise me now if the question of the whole point was raised. This criticism is legitimate. Isn’t the effort to memorize this sequence of symbols too great? Doesn’t the amount of information actually increase? The Sequence-10 or a bit more can certainly still be internalized through popular rote memorization by repetition. For the Sequence-100, however, I assert there is no good alternative to some mnemonic technique. The question, therefore, is either mnemonic technique or no internalization at all. Moreover, after a certain, usually not long, period of practice, mnemonic techniques require significantly less effort than at the first attempt.

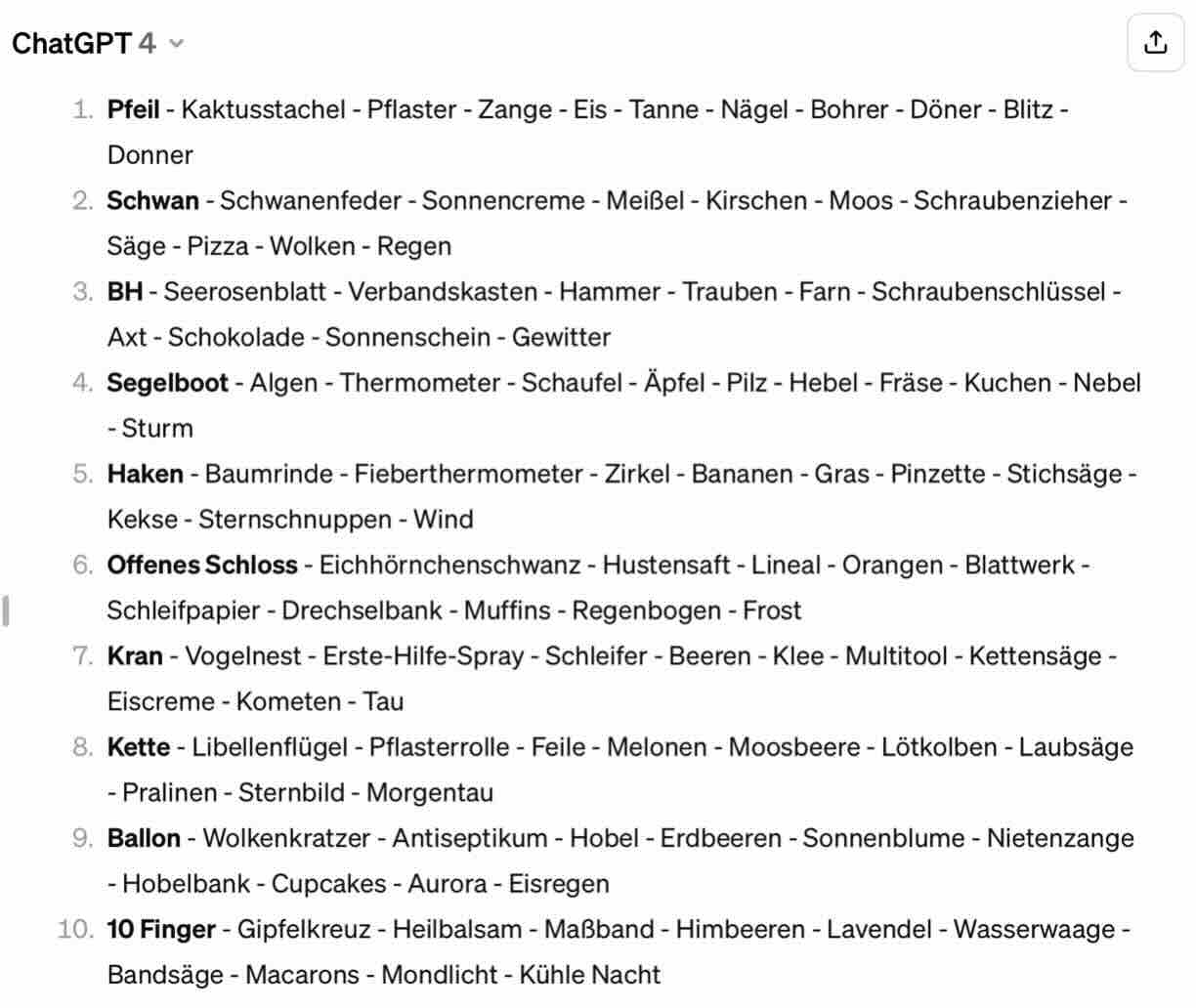

Nowadays, AI, such as ChatGPT, can provide excellent support as well. The imaginative chains it creates can be well adopted and used as a basis for construction. After a bit of back and forth, I received the following list, which can next be transformed into stories or simpler chains of concepts, certainly with the help of AI as well:

Fig. 1: A chain generated by ChatGPT 4

Fig. 1: A chain generated by ChatGPT 4

Outlook

I find it hard to believe that at least the number-symbol route has not remained in everyone’s memory by now. As a very simple exercise, you could try to memorize a shopping list with its help. Start with ten items, so one per route point, and try to figure out from how many items per point it becomes uncomfortably difficult.

In addition to a route as a storage location, we also learned that the mnemonic as the smallest mnemonic technique is always useful again. In German, it’s much more aptly called “Eselsbrücke,” which in English means something akin to a “donkey bridge,” a term that humorously implies it’s a help for donkeys, or metaphorically for those who have a hard time remembering, making it easier for them to “cross over” the gap of forgetfulness. Visualized or sensually perceived objects can be connected, condensed, located, and abstract information logically constructed into and deconstructed out of our brain.

Unless alternative suggestions are submitted to me via the comments function, I would next use more practical examples from the field of memory art, such as a deck of cards, that is a sequence of 52 cards, or how a speech of any length is memorized.

The principles conveyed, etc., should now definitely be consolidated through tasks, and the Sequence-100 should be attempted as one of the exercises. I started this way too.

The real dilemma lies in our education system’s overemphasis on internalizing information, a task more efficiently managed by technical storage media. I present techniques of the art of memory because, despite this, they remain crucial for success in many exams – a necessity for which I am not responsible, but must respond to.

Go to: Learning Platform (LMC)